Breadcrumbs

Cultural policy of Kyoto for the web

Kyoto and its Cultural Policy

Written by Nobuko Kawashima, Professor, Doshisha University

(This report presents the personal views of the author. It does not represent the views of ICCPR or the Japan Association of Cultural Policy Research.)

- Welcome to ICCPR in Kyoto!

- WHY KYOTO?

- Kyoto‘s response to the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on artists

- Crowdfunding the revitalization of cultural activities in Kyoto

- I. PRIVATE VENUES OF CULTURAL DISTRIBUTION

- II. HIGH-QUALITY PROJECTS FOR ARTISTIC DEVELOPMENT

- Conclusion

Welcome to ICCPR in Kyoto!

Although this year‘s conference is being conducted entirely online, we hope that you will feel like you are visiting Kyoto! Kyoto has many distinctive features that we think make it a perfect place for hosting this conference.

WHY KYOTO?

- As Kyoto was Japan‘s capital for over ten centuries, from the year 794 to 1868, it is home to prominent national cultural institutions, historical monuments and sites, numerous temples, shrines, and gardens, and workshops of traditional arts and crafts. The city and surrounding area boast seventeen UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

- Kyoto is also a major player in popular culture. The city‘s Uzumasa neighborhood was home to a thriving film industry between the 1920s and 1960s, when it was known as “the Hollywood of Japan,” and many period dramas are still filmed in Toei Kyoto Studio Park, or “Eiga Mura.” Kyoto Animation Co., Ltd. (“KyoAni”) is one of Japan‘s leading and most innovative anime studios, and game maker Nintendo is headquartered in Kyoto.

- Kyoto is rich in traditional arts, crafts, and food-related industries. Many Noh theatre actors, Japanese tea ceremony masters, and other practitioners of traditional arts reside in Kyoto, including a number who have been designated Living National Treasures by the Japanese government. Kyoto‘s traditional arts and their creators have recently been “discovered” by multinational corporations and used in product design for luxury brands such as Fendi, Louis Vuitton, and Dior, and in the interior decoration of international five-star hotels.See the images at HOSOO, a traditional textile brand in Nishijin, Kyoto.

https://www.hosoo.co.jp/en/ - Another mark of Kyoto‘s importance in terms of Japanese culture and cultural policy is the planned transfer from Tokyo to Kyoto of the Agency for Cultural Affairs (ACA), a special body of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology whose mission is to promote Japanese arts and culture. This is the first move of a central government function to a city outside Tokyo since the national government relocated from Kyoto to Tokyo in 1868. In preparation, the ACA set up a Cultural Policy Office for Local/Regional Regeneration in Kyoto in 2017; the transfer will be completed in 2023.

- As many as 40 universities and other institutions of higher education and research are located in Kyoto, giving the city the highest student-resident ratio in Japan. Of these, at least seven are universities or colleges for the arts.

- Among the major cultural institutions that the city funds and directly manages are ROHM Theater Kyoto (originally Kyoto Kaikan), Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art, Nijo Castle, Kyoto City Zoo, Kyoto Concert Hall, Kyoto City University of Arts, Kyoto Art Center, and the City of Kyoto Symphony Orchestra.

Kyoto thus uniquely combines traditional and contemporary culture, and the arts and the commercial, including the global business of the cultural industries, a fact which requires municipal and prefectural authorities to have a strategy for a “creative city.” Kyoto has been cautious, and relatively slow to devise explicit policies and strategies for developing its creative economy. A strategy for the cultural economy has emerged, however, presenting an interesting opportunity for research into how the city is using its cultural resources in local economic development.

Kyoto‘s response to the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on artists

As elsewhere, cultural facilities such as museums were closed and performing arts events cancelled to prevent spread of the coronavirus, particularly in April and May of last year. The city was quick to take action in the form of distributing grants of 300,000 yen (approx. 2,310 euros) to 1,011 individual artists, artistic projects, and cultural groups and organisations across various disciplines, including visual arts, music, theatre, dance, and photography. This was irrespective of artistic quality, as the purpose of the scheme was to financially support artists whose working contracts had been cancelled due to the pandemic. 300,000 yen is clearly not enough to live on for very long, but the speed at which the grants were provided exceeded that seen for other cities or the national government.

Following this, the city conducted a major survey of Kyoto-based artists and cultural organisations to better understand the economic losses they were suffering, the problems they faced, and the kind of support they needed most. The survey results made clear the seriousness of economic difficulties artists were facing, leading to the launching of an innovative crowdfunding scheme, described below. At the same time, the city opened a support center to provide advice and information to artists on how to take advantage of national government funding programs. Grants were also provided to help cultural facilities take disinfection measures and install necessary equipment. As many artists were not well-equipped to distribute their work or activities online, three models of online artistic distribution were funded to present examples that people could learn from, and a series of seminars was held on methods and techniques of online distribution for artists. Cancellation fees charged by city facilities for cultural activities from February to September 2020 were waived.

Crowdfunding the revitalization of cultural activities in Kyoto

What I personally find particularly interesting as a support measure is the city‘s use of the crowdfunding platform READYFOR and public expenditure to match it. Crowdfunding initiatives were launched in two categories: one for private venues like theatres, clubs, art galleries, and cinemas that offer artistic/cultural content to the public, and the other for projects of high quality that will contribute to artistic development in Kyoto.

This programme makes use of a complicated (some might say bizarre) government tax scheme called furusato nozei, via which individuals can donate to a local city or prefectural government of their choice, not one where they live, and the amount of their donation is deducted from their income and local taxes. In short, part of the taxes they pay go to the government of a city or prefecture other than the one in which they reside. Excuse me if this is incomprehensible! The point is that there is no substantial cost to making donations through this system, as the amount you donate is deducted from taxes that you have to pay anyway. READYFOR matches donors with projects that seek funds, and the city of Kyoto matches donated funds. Both initiatives set a target of raising 10 million yen, which together with matching funds from the city would come to 20 million yen (approx. 154,000 euros) for each. And both initiatives were successful in reaching their goal.

Thanks to this crowdfunding scheme, people from across Japan came to know about the challenges that creators and culture-related organizations in Kyoto are facing, and chose these particular initiatives, from among the many causes competing for donations on the READYFOR platform, to contribute to. Interestingly, the recipients of the donations (and the matching funds from the city) are purely private, which normally falls outside the scope of public cultural policy. I think Kyoto is to be lauded for recognizing the importance of these “private,” often small-scale, actors, which play such an important role in nurturing young artists.

I. PRIVATE VENUES OF CULTURAL DISTRIBUTION

The number of beneficiaries in the first category of the crowdfunding project was 75, with each receiving 320,000 yen (approx. 2,465 euros). These venues, scattered across the city and serving local residents who are not necessarily culture aficionados, are an important cornerstone of Kyoto‘s cultural ecosystem. The fact that “live houses”—small-scale, club-like venues for emerging bands and performers—are included in the project is noteworthy, as these venues have been publicly discredited: they were among the first places to give rise to clusters of COVID-19 infections in Japan in March of 2020.

To get to know more about what these crowdfunding recipients do, I visited some of them taking a photographer with me.

1. DELTA / KYOTOGRAPHIE Permanent Space

Kyotographie is an international photography festival held annually in Kyoto. Started in 2013 by Lucille Reyboz and Yusuke Nakanishi, and drawing on the international connections of the two founders and directors, the festival invites well-established photo artists from all over the world and presents their work at various venues around Kyoto, including places that are not normally open to the public, such as the former printing press room of the Kyoto Shimbun newspaper and old private homes. According to Nakanishi, “our mission is to democratize art, and to emancipate photography from the confining white square to where people lead their daily lives.” The contrast between the photographic works and venues where they are displayed is a major attraction of this festival, which runs for around a month in the spring and attracts many visitors from Kyoto, other parts of Japan, and abroad. Reyboz and Nakanishi start with an annual theme, such as “vibe,” “vision,” or “our environments,” and search out relevant works from Japan and around the world. When photographers agree to exhibit their works, matching venues, most of which are not art galleries, are sought. Nakanishi is proud of this meticulous method of creating a festival, even though it is time-consuming. Considering the scale of Kyotographie, it is surprising that until recently it received no public funding, being financed only by ticket sales and corporate sponsorships. With the success of the festival, which is temporary in nature, the organization acquired a permanent space in September 2020 that combines the functions of gallery, café, and accommodation for visiting artists. The Kyotographie website has limited information in English, but it gives you a feel for what the festival is like.

https://www.kyotographie.jp/stories/

2. Yuuhisai Koudoukan

Set amidst a quiet residential area just west of the Imperial Palace, Yuuhisai Koudoukan has been brought back to life as a research centre and venue for cultural events. It was originally a centre of learning established by the scholar and cultural connoisseur Kien Minagawa (1734-1807). The original building and beautiful garden were at risk of being destroyed for development in 2009, but were saved when a group of citizens got together and raised funds to preserve them. They turned the premises into a venue for cultural activities such as seminars, exhibitions, and workshops. Taking advantage of the wealth of cultural talent in Kyoto, these activities range from Noh theatre and tea ceremony to Japanese confectionaries and traditional kimonos. Research is also a vital part of Yuuhisai Koudoukan, making it an arts centre as well as a salon for Japanese traditional culture. It is managed and funded on a voluntary basis, with limited revenue from the holding of events. Its English website includes a non-verbal video showing what tea ceremony is like. The Japanese website has many pictures and videos.

https://kodo-kan.com/english/index.html

https://kodo-kan.com/

3. Gallery TOMO

Gallery TOMO is a small, commercial art gallery with a focus on contemporary art. The gallery presents works of upcoming Japanese artists whose potential goes beyond Japan, as well as artists from overseas. Owner Tomoharu Aoyama is keenly aware that many graduates from art schools in Kyoto give little thought to pursuing a career as an artist; they have no idea what it‘s like to work as an artist, and they receive little career guidance from their schools. Very talented graduates move to Tokyo where artistic networks and opportunities are more abundant, but it is important for Kyoto to produce young artists too. With a special grant of 300,000 yen that barely covers the cost of renting a small booth, Aoyama is preparing to participate in Art Fair Tokyo 2021, with the aim of being recognized as an important art gallery in the minds of collectors who will be browsing at the fair. He will load the works he plans to exhibit into a mini truck and drive 500 km to Tokyo in late March.

https://gallery-tomo.com/category/artist/

4. UrBANGUILD

UrBANGUILD is a multi-disciplinary art space that presents shows by bands, dancers, and other kinds of performers. It is a private venue run on ticket sales revenue shared with performers and the sale of food and drinks to audience members and other customers. Ryotaro Sudo, the booking manager of this underground space, supports graduates of performing arts universities in Kyoto who, like their visual arts counterparts, have no idea how to plan a career. The experience of auditioning or performing at UrBANGUILD makes graduates realise how protected they were at university; now the quality of their performance is professionally assessed in terms of whether people will pay to see it. For simple performances, Sudo does the acoustics and lighting himself to save money; he enjoys doing this, regular customers and other people volunteer to help, and engagement with the community grows.

http://urbanguild.net/

5. Kyoto Butoh-kan

This is a truly unique theatre—converted from a historical warehouse of an Edo merchant—which is solely dedicated to the performance of Japanese butoh, an avant-garde dance form developed in Japan. It seats only eight (!), enabling an intimate engagement between performers and audience. Prior to COVID-19, performances were held three times a week, attended by cult fans from Japan and abroad (including a well-known Hollywood celebrity!), who travel to Kyoto to experience authentic butoh performance here. In fact, 70 percent of the audience was non-Japanese. The Butoh-kan website has a lot of information in English, including a short, non-verbal video.

https://www.butohkan.jp/

II. HIGH-QUALITY PROJECTS FOR ARTISTIC DEVELOPMENT

The second category of the crowdfunding project was more selective. It funded only eleven artists and groups out of 106 who applied, based on artistic quality and innovativeness. I also visited a few of these funding recipients to learn about their projects and future plans.

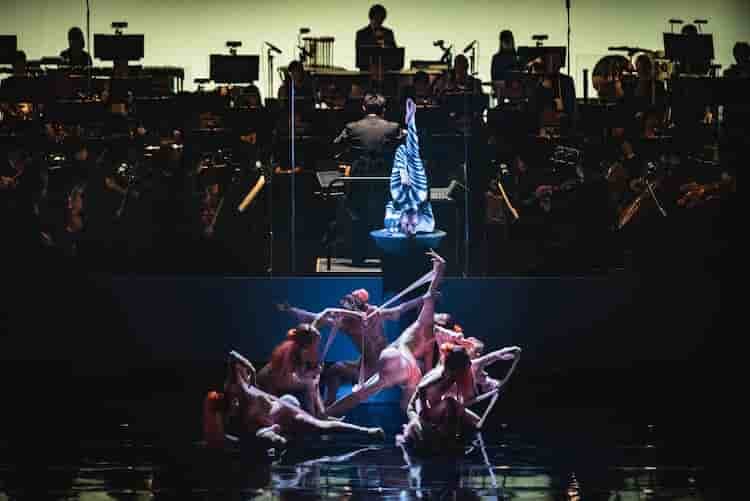

1. Hibiki Sato and Kotaro Kawamura

Hibiki Sato, an active cellist based in Kyoto, and Kotaro Kawamura, born into a Noh theatre family and a performer since childhood, met at a darts bar one day and hit it off as artists of the same generation. Sato organized a collaborative event between the two involving Western classical music and Noh theatre, a traditional Japanese high art form with a six-century history. Having lost many opportunities to perform in public due to the coronavirus, they presented an unlikely performance in which Noh theatre was accompanied by Western musical instruments such as cello and flute. It was successful, and having seen DVD, I find the performance (with talks by the performers) fantastic, but Sato was not totally satisfied with the result (or he is more ambitious): he does not think the two different disciplines successfully broke out of their respective frameworks to create something entirely new. Noh has been perfected over the centuries through a reductionist approach, and adding to it a Western tradition with different notions about music turned out to be quite difficult. Sato reckons it was a great experience, however, and the two performers will continue the challenge of exploring how to work together.

See an abridged version of the performance.

https://youtu.be/NCSrj2-YjeI

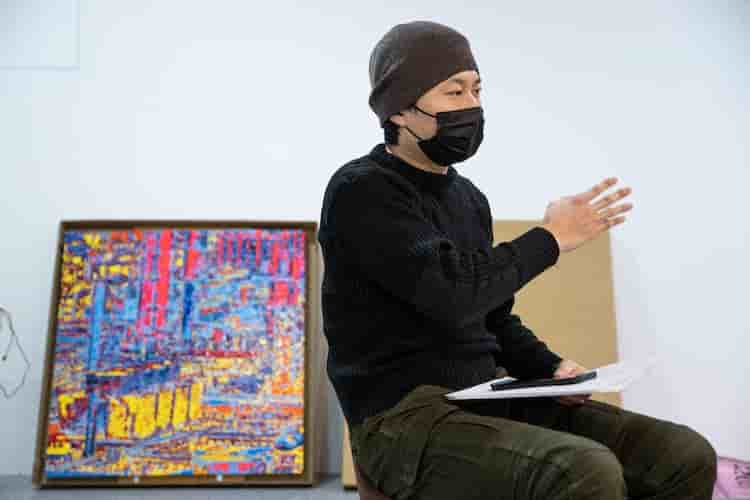

2. Daisuke Kuroda “Gallery Truck”

Faced with the difficulty of exhibiting in galleries and getting people to come, Daisuke Kuroda, a multi-media artist whose works have been shown in major galleries, came up with an innovative way to show works by contemporary artists he is friends with: he drives a mini truck around Kyoto with pieces of art—sculpture, videos, paintings, etc., depending on the day—installed on the truck bed. He operates the truck in the usual way, not stopping intentionally to grab the attention of pedestrians. Art is usually appreciated in an “institutional setting,” Kuroda explains, with the audience starting out with the intention of taking in works of particular artists or styles in a quiet, intensive way. With the “Gallery Truck,” art is encountered in a momentary, unexpected, and unplanned way, thus challenging conventional art institutions.

“Gallery Truck” is not just an outreach project, but the truck with art running around in the city itself is an art work. See what it is like:

https://sites.google.com/view/trucktrucktruck

3. Yu Tanaka

Yu Tanaka heads a troupe of performers who re-create plays (which in fact amounts to inventing new plays) via an unusual method: filming bits and pieces at different locations and combining them later in a studio. In his current, funded project, he mixes Japanese mythology with the story of two Kyoto elementary schools which have closed due to the decreasing number of school-age children in their neighbourhoods. The play incorporates videos, dance, and reading.

Tanaka is grateful for the funding he‘s received from the city of Kyoto, but believes the application process could be improved. The lead time for conceiving the project and writing the application was rather short, while booking performers and a venue had to go forward regardless of the outcome of the application. Most of all, it was unknown whether the crowdfunding effort would succeed in reaching its target amount of money raised. Tanaka thought, “Well, let‘s give it a go anyway,” but not everybody can live with that kind of uncertainty.

Conclusion

Through these interviews, I met a number of artists and arts managers in Kyoto in a variety of disciplines whose dedication supports the lively arts scene of this city. The city‘s response to COVID-19 in terms of cultural activities has been remarkable—a rare coming together between public officials (who are not arts professionals) and artists with passion, visions. and energy. Kyoto does not have an arts council-style organization with professionals who understand the needs of artists and speak for them, and who can mediate between local authorities and artists. I think the unusual encounter between government and the arts that the pandemic has engendered offers a very good lesson for Kyoto‘s cultural policy, and I hope that the experience of the past year will enrich that policy in the near future.

Photo credits

- (6) Shigeo Ogawa

- (7) yamaji kenta

- (15)(16)(17) provided courtesy of KYOTOGRAPHIE

- (20)(21)(22) provided courtesy of Yuuhisai Koudoukan

- (28) Shinpei Murayama

- (32) Tomoko Kosugi

- (33) Kyo Nakamura

- (1)~(5), (8)~(14), (18), (19), (23)~(27), (29)~(31), (34)~(45) Toshiaki Nakatani